Invasive Species

---11.14.1999---

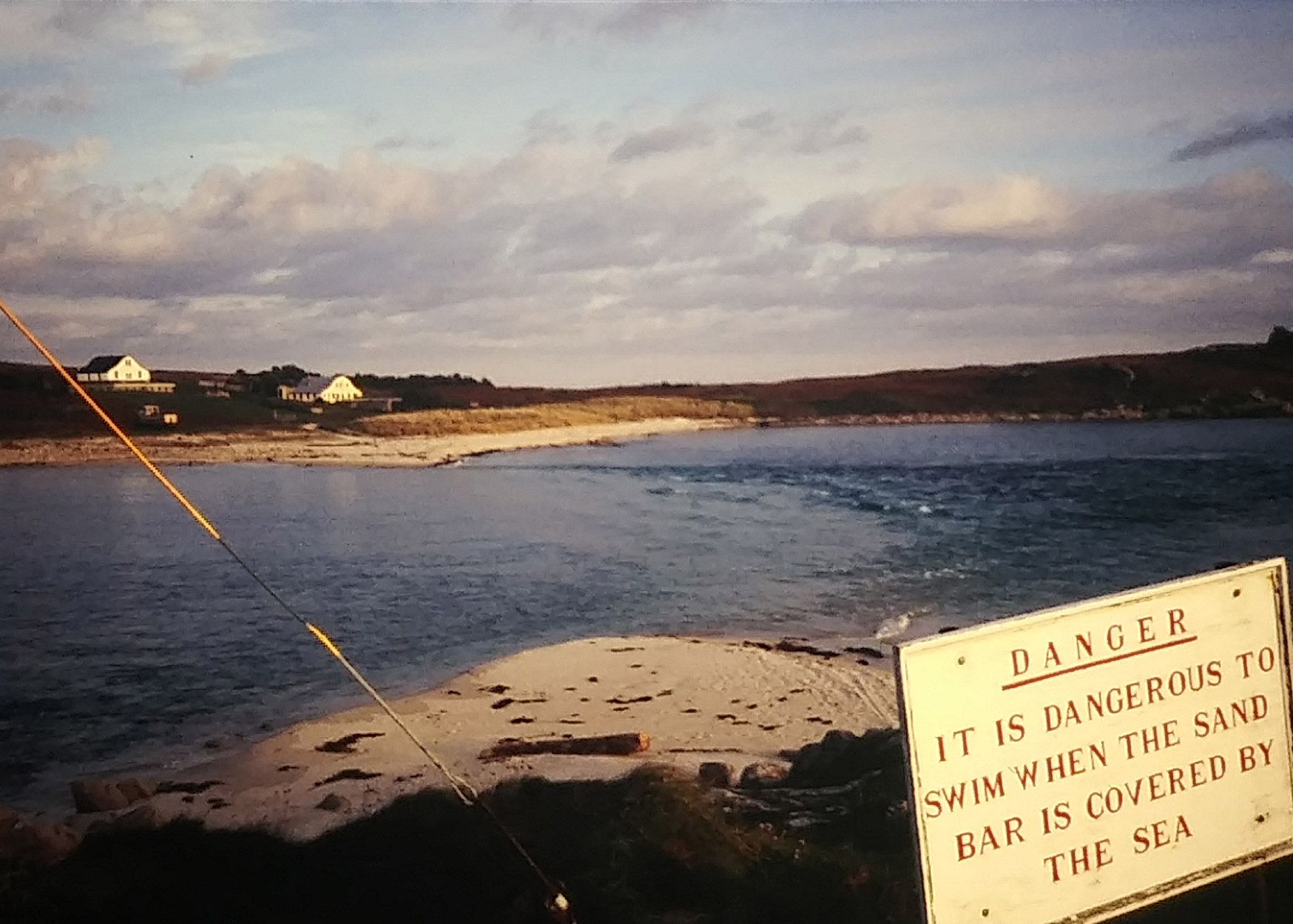

I came across an injured seal pup today on Gugh, St. Agnes’ largely unpopulated Siamese twin. Twice a day a high tide cuts, or rather covers, the sandbar linking the two islands, and Gugh is left to float freely for a few hours. It’s nice to go for a walk there sometimes, though you have to consult a tide chart before you set off to ensure you’re not left stranded there on the homeward leg. I read the chart this morning (incorrectly, as I later found out), topped up the heating oil for the stove, and set off.

There are two parallel trails that run down to the sandbar. Jon is superstitious about taking one of them—I forgot which. Where the trail splits, I headed down to the right. A few paces on, I remembered this was the trail he never took. "Well shit," I thought and made a mental note to take the "lucky trail" next time. I trudged across the now broad sandbar and, at the far end, sank my right boot into a drift of really rotting, really smelly seaweed. Yiiiiuuuck! I wiped the muck off of my foot as I walked up the grassy slope.

Gugh is about two-thirds the size of St. Agnes but supports only two houses, which lie at the far end of the bar. The rest of the island is gently rolling, natural terrain covered with springy moss and a brown fern that looks so suspicious in this setting. The trails there are either broad and grassy or single paths cut deep into the soil. As I walked, I thought about how many feet, over how many centuries, had carved these trails into the hillsides. Further up the path a couple of rabbits spotted me and darted off into their burrows. It was overcast and windy this morning, and I was just warm enough, wearing two sweaters and long underwear, still I kept up the pace to raise my body temperature a little.

I came to a spot on the trail on the edge of a small cliff that dropped off maybe ten feet or so to the rocky beach. The cliff formed a sort of parabolic curve, and I stepped off of the trail a bit to see what was at its apex. It turned out that the face of the cliff was undermined at that point, and the further I walked, the more I could see that a cave or tunnel had formed on that point on the beach, and that it was filled with the remains of some sort of age-old equipment. Curious, I followed a thinly trodden path along the ledge to a point where I could get down to the beach. After walking a few boat-lengths, the height of the cliff had trailed off to basically nothing, and I made for a little ledge from which I could jump down to the shore. And there was the seal.

“Oh no... Oh no...” I gasped under my breath. It was so little, all gray, black, and white, and covered with fuzzy baby fur. I walked around it to see if it was alive. It saw me immediately, lifted its head, and plaintively groaned. I just stared blankly, and it groaned some more. “Oh shit...,” The "what to do when you come across an injured seal" part of my brain was totally empty. I slightly panicked when I checked there and heard only a hollow echo. What to do? What to do? It groaned some more. It felt so amazing to be so close to this little animal—its eyes, its whiskers, its teeth, the roof of its mouth (that looked like a dog’s). I didn’t want to get too close, but I could see that one of his front flippers looked injured. I left the seal there, ran back across Gugh, and over the sandbar, to try and find Ellen and Bryce in hopes they might know about this kind of thing.

After a long slog, I was back at our part of the island. Ellen was home, and I explained the situation to her. Only having moved here two years ago, her seal knowledge was as weak as mine, so she called James Ross, a farmer whose family has been here for centuries. "Uh-huh... right... mmm... I see." He suggested just leaving him there, as his mother might be close by. Apparently, when seal pups are sometimes "rescued," their mothers can be seen roaming the coast, barking, still searching for their missing kids. So we left it there.

------

Later in the afternoon another expedition was formed to go check on the seal. Phillip, my roommate who moved in a few days ago, was intrigued. "Can you describe where it is? I want to photograph it. I’ve taken a lot of photographs of dead or injured animals on the islands." I couldn’t believe it! I felt like I was talking to the producer of "The World’s Most Shocking Animal Photographs!" The only reason I agreed to show him was that he suggested we ask Patricia, one of the two people who lives on Gugh, to see if she might know what to do. So we set off: Phillip, his friend Ben, who was visiting for the weekend, and me.

We got to her house, an old concrete barn converted into living quarters in the seventies, and knocked at the back door. She seemed like a kind, practical woman, perhaps in her early fifties, with short hair and glasses. She suggested going to see how the pup was doing and, if it was in bad shape, to come back and call the seal shelter on the mainland and ask their advice.

The seal was still there and began groaning at the sight of us. On second look I couldn’t really see an injury. One flipper was slightly goopy looking but very much intact. It seemed uneasy with the three of us surrounding it, so Ben left to go climb a rock formation on the other side of the cove. I backed away a little as well, and Phillip took photographs. At that point the seal had had enough, left its grassy perch, and started heading across the 50 yards of boulders to try and get to the sea. We retreated, hoping it would retake its position, but it didn’t. Perhaps it wasn’t injured at all. Maybe it was just hanging out, waiting for its mama to get back from fishing or something. Phillip and I climbed the nearby granite outcropping to watch. We could see the pup awkwardly navigating the large, round stones. My heart sank. At that time in the afternoon, the tide was at its lowest point, and the seal had a long way to go. Eventually we lost sight of it and headed back down the rock.

You hear about the damaging effects of invasive species on natural locations, and here I am, an invasive species. Had I not arrived and not taken a walk on Gugh that morning, a seal pup would not have risked making a dash for the water at low tide. Sheesh. I hope it made it.

------

Life and death are abundant all over these islands, but especially on Gugh. Walking back, we came across several random bones, pieces of vertebrae, and delicately linked sections of skeletons. The most dramatic were the remains of a sea gull, its wings splayed out like an angel’s and its spine, still attached to the wing structure, sticking out vertically from the ground. It looked like it had crashed headfirst into the soft soil and another animal had come along and picked it clean.

Further along, we came to a standing stone called "The Old Man of Gugh." As an object, it’s only mildly impressive: a man-width slab of granite standing about seven feet tall, leaning towards the east. The far more curious thing is that it is said to mark the spot where five ley lines converge and is thought to have been put there in Neolithic times. Why were these ley lines so important that the spot had to be marked with a sizable slab of granite? What had happened at this spot millennia ago? It is also said that around that time the seas were shallower and Scillonia was connected to mainland England forming the top of a mountain range.

Ancient people were said to have buried their kings here on the top of Gugh, still one of the highest points in the islands, and oriented the burial chambers towards the sea. And indeed, you can still see these empty chambers and the scant remains of stone walls today. The largest one, set into the side of a cliff on Gugh’s westward slope, is a partially collapsed post and lintel structure about ten feet long, four feet wide, and three feet tall. Most appear to have been ransacked in the last few hundred years. I heard that this particular site offered up some funerary urns in the 1800s. It amazes me to think about the people who lived here then. I’ll have to learn more.

Member discussion